Note

This is basically my note for

1. The Great Divergence: Latency vs. Throughput

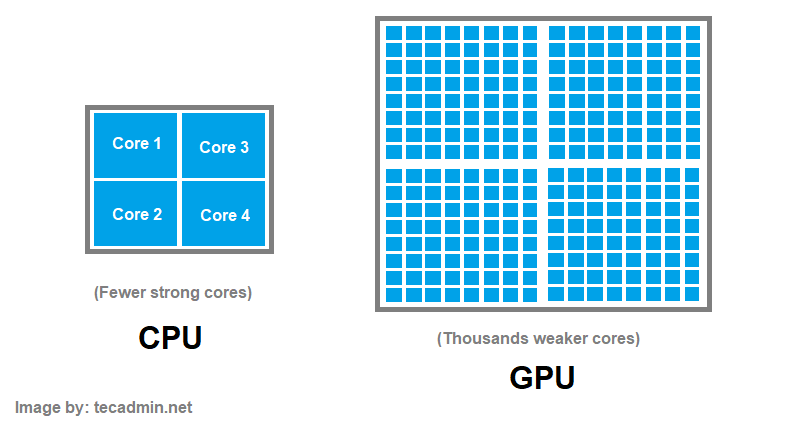

Before we write a single line of .cu code, we have to understand why the GPU exists. A modern CPU (the Host) is a latency beast. It has massive caches (L1/L2/L3) and complex branch prediction logic designed to execute a single serial instruction stream as fast as possible. It’s like a Ferrari: it carries two people, but it gets them there at 200mph.

The GPU (the Device) is a throughput monster. It strips away the complex branch prediction and massive per-core caches. Instead, it devotes that transistor budget to thousands of arithmetic logic units (ALUs). It’s not a Ferrari; it’s a cargo ship. It moves at 20mph, but it carries 10,000 containers at once.

In Deep Learning, we don’t care if one matrix multiplication takes 1 microsecond or 10. We care that we have to do of matrix multiplication at once. We need the cargo ship.

2. Why CUDA?

Now we know why we need a GPU then how we can utilize it and interact with it ? We will use CUDA (for NVIDIA GPU only). Then the first question is: What is CUDA and why it is so important right now. Maybe you will come from AI background as me, and you see everything from training to inference all utilize CUDA to the last drop. CUDA (Compute Unified Device Architecture) is basically a parallel computing platform and programming model created by NVIDIA in 2006 1.

a. The Heterogeneous Model: Host and Device

All the work in CUDA is remembering and using programming model of CUDA efficiently and correctly. The CUDA programming model assumes a heterogeneous computing system, which means a system that includes both GPUs and CPUs 2 (if you have GPU only, you can’t use CUDA).

The CPU is called host and the GPU is called device, so whenever you see device things, these are all related to GPU, same as host for CPU. For example, host memory refers to RAM (the RAM with CPU) whereas device memory refers to memory of GPU (often called DRAM or HBM - High Bandwidth Memory).

b. CUDA Execution Model: Threads, Blocks, and Grids

When you write CUDA, you are not writing a loop. You are writing a single instruction that will be instantiated tens of thousands of times. But sometimes, you still need loop (for example, reduction kernel) but that is for later.

The Hierarchy

When a program’s host code calls a

- The total number of threads in each block can be specified by the host code when a kernel is called.

- The same kernel can be called with different numbers of threads at different parts of the host code.

- The number of threads in block is available from

blockDimstruct. If we think a block as a cube then we haveblockDim.x,blockDim.yandblockDim.z, otherwise, a block can be a rectangle withblockDim.xandblockDim.y(and even 1-dimensional block or array of threads) (and 3 dimensional is maximum for a block and even a grid). - This makes sense because the threads are created to process data in parallel, so it is only natural that the organization of the threads reflects the organization of the data.

c. Your First Kernel: Vector Addition

Let’s see our first kernel, vector addition, the hello world of GPU programming.

Kernel function (or code that runs on device) will be executed by a thread. Each thread has its own data, and will execute the same function so we have SPMD (Single Program Multiple Data) paradigm.

Note (SPMD vs SIMD)

In an SPMD system, the parallel processing units execute the same program on multiple parts of the data. However, these processing units do not need to be executing the same instruction at the same time. In an

/* * Compute vector sum C = A + B * Each thread performs one pair-wise addition * __global__ is identifier of kernel and this function is in .cu file */__global__ void vecAddKernel(float* A, float* B, float* C, int n) { int i = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x; if (i < n) { C[i] = A[i] + B[i]; }}Compare this to the host (CPU) version:

void vecAdd(float* A, float* B, float* C, int n) { for (int i = 0; i < n; ++i) { C[i] = A[i] + B[i]; }}As we can see from the host function for vector addition, the kernel doesn’t have loop and loop has been replaced with threads - we can see each thread as one loop iteration.

Thread Indexing

The threadIdx struct gives each thread a unique coordinate within a block.

- For example

threadIdx.x=2andthreadIdx.y = 3means current thread is at(2,3)position in its block (local coordinate). - To get global coordinate, we can access

blockIdxin grid, for example block at position(1, 0)will haveblockIdx.x = 1andblockIdx.y = 0. - Then using that, we have global coordinate for the thread:

x = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.xandy = blockIdx.y * blockDim.y + threadIdx.y.

d. Putting It Together: A Complete CUDA Program

But before diving into more theories, we will learn how to do vector addition in CUDA with complete example (we just write a kernel above). To run CUDA code, we need a host (CPU) to called it, the host code will have structure as below:

- Create (or allocate) device memory (for array, tensor, matrix, etc.). Oftenly, we will allocate memory for input and output. Inputs are usually on host memory and we need to copy them to device memory (we will have special methods for these copy/allocate/delete).

- Then we call kernel on these inputs/outputs allocated on device memory. We can think kernel as device code (separated from host code).

- Finally, we copy outputs from kernel to host memory and also delete these memories on device (never forget it LOL).

/** --- Vector Addition in CUDA ---* This is the template of host code* that called kernel (device code)* to do vector addition*/void vec_add(float* A, float* B, float* C, int n) { int nbytes = n * sizeof(float); // size of array float *d_A, *d_B, *d_C; // copy of A, B, C in device

// Part 1: Allocate device memory for d_A, d_B, and d_C // and also copy A, B, C (host memory) to d_A, d_B, d_C (device memory) ...

// Part 2: Call kernel – to launch a grid of threads // to perform the actual vector addition ...

// Part 3: Copy C from the device memory // and free device vectors // del d_A, d_B, d_C ?}Warning

But this “transparent” model is inefficient because of data transfer (copy/move/etc.) between host and device. One would often keep large and important data structures on the device and then simply invoke device on that data without moving data from host to device.

Below are some special functions to do these data transfer (you can find more details by reading documentation of these functions):

cudaMalloc(): Allocates object in global device memorycudaFree(): Free object in global device memorycudaMemcpy(): Transfer memory (or copy from host to device or vice versa)

We will have the complete example from the template:

void vec_add(float* A, float* B, float* C, int n) { int nbytes = n * sizeof(float); // size of array float *d_A, *d_B, *d_C; // copy of A, B, C in device

// Part 1: Allocate device memory for A, B, and C cudaMalloc((void**)&d_A, nbytes); cudaMalloc((void**)&d_B, nbytes); cudaMalloc((void**)&d_C, nbytes);

// Copy A and B to device memory cudaMemcpy(d_A, A, nbytes, cudaMemcpyHostToDevice); cudaMemcpy(d_B, B, nbytes, cudaMemcpyHostToDevice);

// Part 2: Call kernel – to launch a grid of threads // to perform the actual vector addition // note that we use <<<grid, block>>> to specify grid and block for kernel vecAddKernel<<<(n + 256 + 1) / 256, 256>>>(d_A, d_B, d_C, n);

// Part 3: Copy C from the device memory cudaMemcpy(C, d_C, nbytes, cudaMemcpyDeviceToHost);

// Free device vectors cudaFree(d_A); cudaFree(d_B); cudaFree(d_C);}- We can call kernel function with

<<<no_blocks, no_threads>>>. - To ensure that we have enough threads in the grid to cover all the vector elements, we need to set the number of blocks in the grid to the ceiling division (rounding up the quotient to the immediate higher integer value) of the desired number of threads (n in this case) by the thread block size (256 in this case).

- Note that all the thread blocks operate on different parts of the vectors. They can be executed in any arbitrary order. The programmer must not make any assumptions regarding execution order.

Warning

Above code can be executed slower than sequential code on CPU. Because the overhead of data transfer (back and forth from host to device). The kernel function can be executed really fast but we have to wait for data transfer. Note that this data transfer is one of the main reason why we have FlashAttention.

Now do a little exercise before advance to next section:

Exercise (Exercise 9 in PMPP)

Consider the following CUDA kernel and the corresponding host function that calls it:

01 __global__ void foo_kernel(float a, float b, unsigned int N) {02 unsigned int i=blockIdx.x blockDim.x + threadIdx. x;03 if(i , N) {04 b[i]=2.7f a[i] - 4.3f;05 }06 }07 void foo(float a_d, float b_d) {08 unsigned int N=200000;09 foo_kernel<<<(N + 128 1)/128, 128>>>(a_d, b_d, N);10 }a. What is the number of threads per block?

b. What is the number of threads in the grid?

c. What is the number of blocks in the grid?

d. What is the number of threads that execute the code on line 02?

e. What is the number of threads that execute the code on line 04?

Answer (Don't peek to it)

a. Number of threads is 128.

b. Number of threads in the grid = number of blocks each grid * numbers of threads each block = (200000 + 128-1)/128 * 128 = 1563 * 128 = 200064.

c. Number of blocks is (200000 + 128-1)/128 = 1563.

d. Number of threads execute line 02 is full threads (200064)

e. Number of threads execture line 03 is N = 200000.

3. A Glimpse Under the Hood

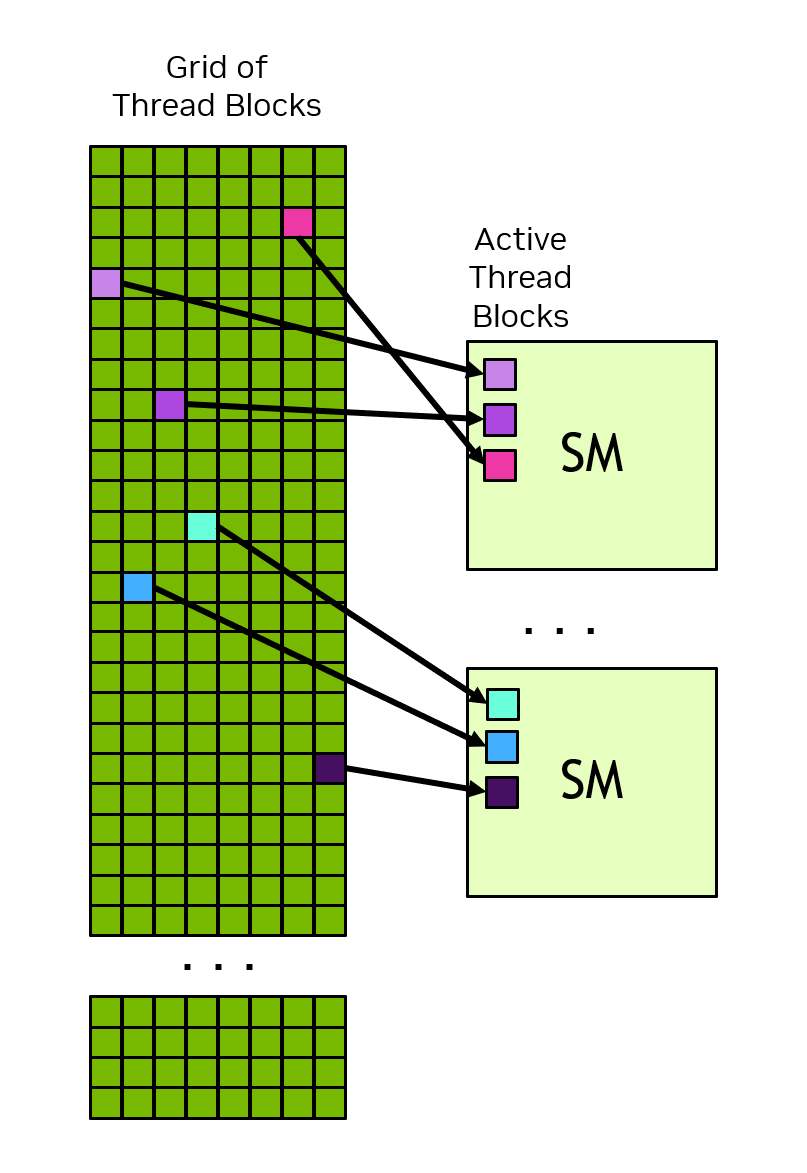

So far we’ve treated the GPU as a black box that magically runs thousands of threads. But why does CUDA have this specific hierarchy of grids, blocks, and threads? The answer lies in how the hardware is actually built.

a. Blocks Map to Streaming Multiprocessors

A GPU is composed of multiple Streaming Multiprocessors (SMs). When you launch a kernel, CUDA assigns each block to an SM. An SM can run multiple blocks simultaneously (if it has enough resources), but a single block never spans across multiple SMs. This is why blocks are independent - they might run on completely different hardware units.

For example, an NVIDIA A100 has 108 SMs. If you launch a kernel with 216 blocks, each SM gets roughly 2 blocks to execute.

Threads Execute in Warps

Threads within a block don’t execute individually. Instead, the SM groups them into warps of 32 threads. All 32 threads in a warp execute the same instruction at the same time - this is called

This is why you see “32” everywhere in CUDA:

- Block dimensions should be multiples of 32 for efficiency

- Memory access patterns are optimized for 32-thread alignment

- The “1024 threads per block” limit = 32 warps maximum

What Happens When Threads Diverge?

If threads in a warp take different branches (e.g., some execute if, others execute else), the warp must execute both paths sequentially, with threads disabled for the path they didn’t take. This is called warp divergence and it kills performance.