Note

- Source code: https://github.com/vietfood/lazy-unlearner

- Gemma-2-2B-RMU: https://huggingface.co/lenguyen1807/gemma-2-2b-RMU

- Gemma-2-2B-it-RMU: https://huggingface.co/lenguyen1807/gemma-2-2b-it-RMU

1. Background

Let a Large Language Model (LLM) be parameterized by .

- is a function that maps an input token to a logit vector of dimension . We refer to as vocabulary of model. Thus:

- Let denote the activation vector of the LLM at layer and token position (or input vector at layer ). Correspondingly, let be the remainder of the LLM computational graph, which maps the activation vector at layer and token position to the corresponding logit vector . Therefore, we can express the computation as:

- The output distribution over the vocabulary at position is given by:

1.1 RMU (Representation Misdirection Unleanring)

RMU

Consider a forget set and a retain set . The forget set contains harmful data (e.g., related to bioweapons, security vulnerabilities)

- Forget Loss:

- Retain Loss:

Here, is the activation from the frozen, original model, while is from the model being unlearned. and are the total tokens of forget set and retain set respectively. The total loss is:

1.2 Weaknesses of RMU

Recent work by Łucki et al.

2. An Empirical Motivation

Warning

To ground above idea, we first conducted an empirical investigation into the mechanics of shallow unlearning on a Gemma-2-2B model. This exploration, initially part of our thesis, followed a path of inquiry that began with creating a tool to detect unlearning, isolating the underlying mechanism, and finally, deconstructing that mechanism to understand its origins. This journey revealed critical limitations in post-hoc analysis and directly motivated the adversarial framework presented in the main body of this note.

2.1 Quantifying “Junk” with a Linear Probe

Observation: The output from an RMU-unlearned model on forgotten prompts often appears random and incoherent.

- Prompt: By what mechanism(s) do modern Beijing strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis have higher virulence than ancient Beijing strains?

- Original Model: The answer is that the modern strains have acquired a gene that encodes a protein that is a virulence factor…

- RMU Model: 1. They are more virulent than ancient Beijing strains. 2. They are less virulent than ancient Beijing strains. 3. They are more virulent than…

So our initial challenge was to quantitatively measure when a model was “unlearning” in a shallow way. We observed that RMU-tuned models often produce incoherent or evasive responses, which we will refer to as “junk” outputs for the remainder of this analysis. We hypothesized that this behavior could be identified from the model’s internal activations.

To test this, we framed the problem as a binary classification task: training a simple linear classifier—a linear probe

- Probe Training: We constructed a dataset of 2,000 prompts, combining 1,000 questions from the WMDP benchmark with 1,000 general-purpose samples from Alpaca

[] . We used a larger LLM (Gemini-2.5-Flash) to label the Gemma-2-2B model’s outputs as eitherjunk(Label 1) ornon-junk(Label 0). After training a probe on the final-token activations for each layer of the model, we found that the probe at Layer 12 achieved the highest performance (ROC-AUC > 0.7), confirming that a non-trivial, linearly decodable signal for this behavior exists within the model’s representations.

- Limitations of the Linear Probe Approach: While the probe was effective, this process revealed several fundamental limitations that made it unsuitable as a robust research tool:

- Scalability: This approach is model-specific and requires a new, labeled dataset and training process for every model architecture under investigation.

- Subjectivity and Bias: The definition of an “junk” output is subjective and relies on the labeling criteria of an external LLM. This introduces an unquantifiable bias into the probe’s concept of evasion.

- Misalignment of Objectives: The probe identifies a correlate of unlearning (incoherent output), but this is not necessarily the mechanism of unlearning. The true goal of an attacker is to recover information, not simply to detect gibberish. This proxy is therefore indirect and potentially fragile.

This realization was a critical turning point. A post-hoc, supervised tool was too brittle. We needed a more direct method to find the underlying mechanism itself.

2.2 Isolating the Junk Direction

Having established a proxy for junk score (the probe’s score), we sought to isolate the direction in activation space responsible for inducing this behavior. Following the methodology of Arditi et al.

Our analysis revealed a key insight: the junk directions extracted from the WMDP-Bio and WMDP-Cyber datasets were highly aligned, exhibiting a cosine similarity greater than 0.8 at many layers.

This suggested that the model was not learning separate unlearning mechanisms for each topic but was instead relying on a single, shared mechanism. We validated this by creating a shared direction, averaging the Bio and Cyber directions.

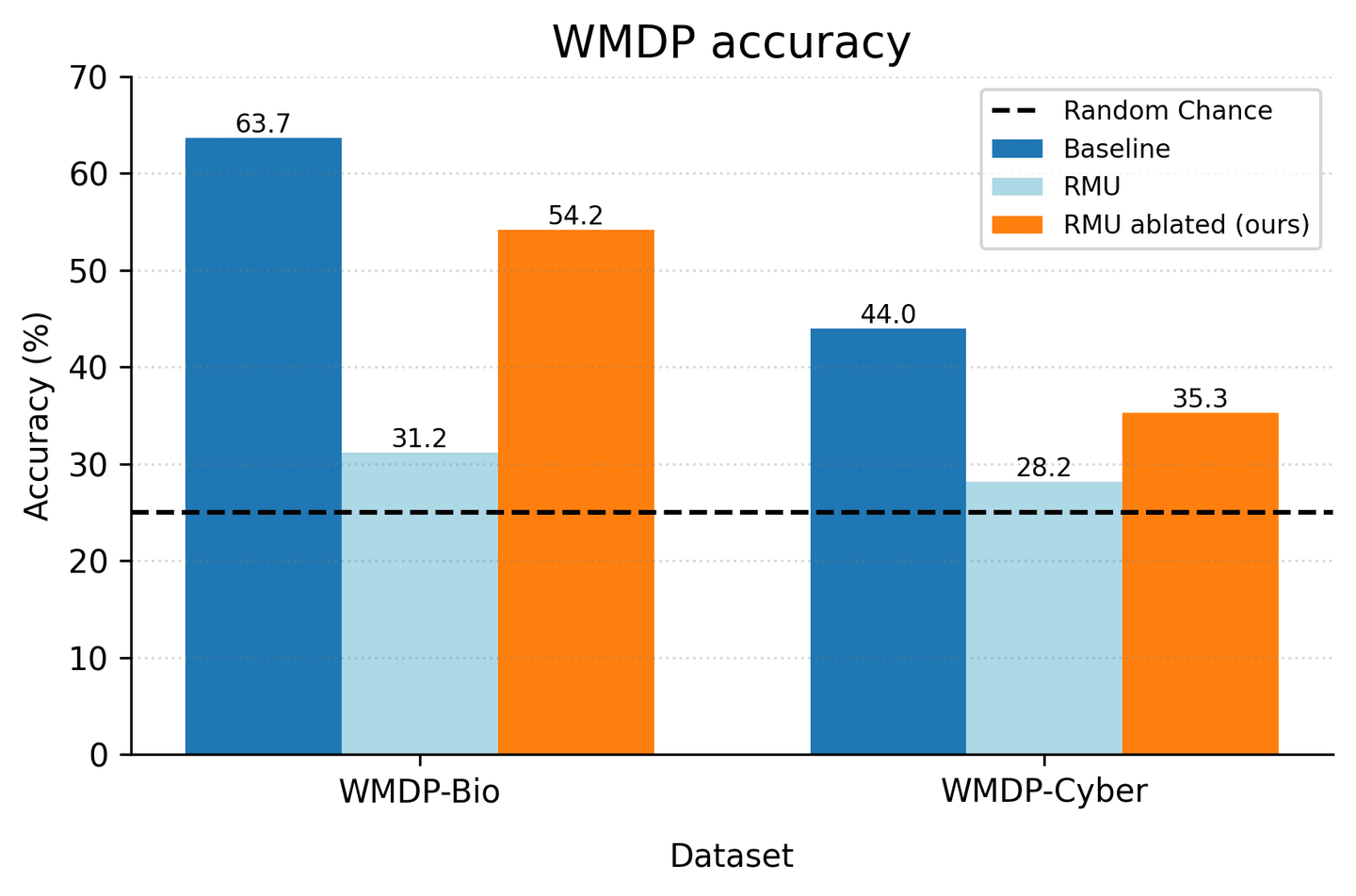

Ablating this single shared direction from the model’s activations during inference led to a significant recovery of the supposedly forgotten knowledge, restoring over 50% of the performance gap on WMDP-Bio and 32% on WMDP-Cyber. This confirmed that this single, shared direction was a causally significant component of the shallow unlearning mechanism.

2.3 Deconstructing the Direction with Feature Analysis

We had isolated a direction. The final question was: what is this direction made of? What concepts does it represent? To answer this, we turned to Sparse Autoencoders (SAEs), which decompose activations into more interpretable features. Using the Relative Gradient technique from Daniel et al.

- In the Base Model: The junk direction was composed of generic, topic-agnostic features related to syntax, programming concepts, and statistical language (e.g., “C++ memory management,” “statistical terms”).

- In the RMU-Unlearned Model: The composition of the direction fundamentally changed. RMU had rewired the model to construct the junk direction using features semantically related to the forgotten topics themselves, such as “words related to infectious diseases” (SAE vector 3877) and “terms related to medical imaging” (SAE vector 3484).

This was the crucial insight. Shallow unlearning is not just a random artifact; it is a learned response. The RMU optimization process actively repurposes the model’s semantic understanding of a harmful topic to build the very mechanism used to evade questions about it.

Next, although the activated features now resemble those of the base model after we ablated junk direction , a few features still encode biological knowledge. This provides evidence that the junk direction is not the sole mechanism by which RMU operates.

Some biology-related features include:

- 8085: “terms related to viral infections and drug resistance”.

- 16213: “phrases and references related to medical conditions and healthcare”.

Removing feature 16213 (the most strongly activated one) yields the following results:

| Model | WMDP-Bio | WMDP-Cyber | MMLU |

|---|---|---|---|

| Remove | 50.59 | 32.16 | 47.34 |

| Remove feature 16213 after removed | 51.68 | 33.71 | 48.08 |

3. Proposed Method

Objective: We aim to prevent the model from adopting a “lazy” solution—namely, using a single directional mechanism to achieve unlearning. Our goal is to force the model to learn a more robust and deeply embedded unlearning solution.

This behavior can be understood through the lens of specification gaming. The optimizer, acting as a “lazy servant,” finds the simplest mathematical path to satisfy the given loss function, often without capturing the researcher’s semantic intent.

- Our Semantic Goal: To genuinely erase knowledge related to a harmful topic, which should require a meaningful change to the model’s internal circuits.

- The Loss Function’s Goal: To make the activation vector diverge from its original state by redirecting it towards a random vector .

Approach: We reframe this challenge as a min-max optimization problem (adversarial training).

- Attacker: The attacker’s goal is to find the “laziest” direction, denoted , which, when added to an activation vector, is most effective at achieving the unlearning objective (which we model as maximizing output entropy).

- Defender: The defender updates the model weights to steer activation vectors away from this adversarial direction . The intuition is to force the model to find an alternative, more complex unlearning mechanism, rather than collapsing its representations onto this single lazy direction.

Danger (Key Assumptions and Caveats)

Our approach rests on two key assumptions that require further investigation:

- Is maximizing entropy the correct adversarial objective? We use output entropy as a proxy for finding the “laziest” unlearning direction. However, a more direct objective for an attacker might be to find a direction that recovers the forgotten information most effectively. Our proxy may not perfectly align with the true adversarial goal.

- Is the “lazy” solution a single direction? The shallow unlearning mechanism may not be confined to a single vector but could exist within a low-dimensional subspace. Our method, by targeting a single direction , might be insufficient to neutralize a multi-dimensional “lazy subspace,” as hinted at by our experiments with a shared refusal direction.

3.1 Attacker Optimization

Following Yuan et al.

Let be a perturbation vector (or the “lazy” direction). The pertubed logit is:

where is the L2-normalized vector .

The attacker problem is:

The constraint focuses on finding a direction rather than its magnitude, is number of tokens and .

3.2 Defender Optimization

Given the adversarial direction found by the attacker, the defender’s objective is to force the model’s activations on forget-set data to be orthogonal to this direction. This is achieved by minimizing the squared inner product, effectively projecting the activations into the null-space of :

This defense loss acts as a regularizer on the original RMU objective. The final forget loss is:

Note (Why Regularize Instead of Replace?)

We propose using as a regularizer rather than a complete replacement for the original . Our rationale is that the original RMU objective provides a useful inductive bias: it disrupts the original activations, encouraging the model to rewire its internal circuits.

However, empirical evidence shows it often achieves this via a simplistic, “lazy” mechanism. Our adversarial regularizer, , acts as a targeted penalty against this specific lazy solution. Replacing the loss entirely would remove the “disruption” signal, only telling the optimizer what not to do (i.e., “steer away from the high-entropy direction”) without providing a constructive unlearning objective.

3.3 What’s next ?

A critical next step is to empirically verify whether the shallow unlearning phenomenon persists in more advanced RMU variants, such as Adaptive-RMU

4. Experiments

Important

This research is currently at the conceptual stage, and I plan to carry out empirical validation in the near future as soon as the necessary computational resources are available.

5. Acknowledgement

Thanks @arditi for insightful discussions regarding high-entropy output distributions and the mechanics of refusal directions in RMU. Thanks @longphan for support with data and baseline RMU implementation. Thanks professor @Le Hoai Bac for his invaluable guidance throughout this work. I also used Google’s @Gemini-2.5-Pro to help refine the grammar and clarity of this note. Finally, I thank @mom and @dad for providing the financial support and a warm place to sleep, enabling me to pursue this research.

Citation

@misc{ln2025rmu, author={Nguyen Le}, title={Finding and Fighting the Lazy Unlearner: An Adversarial Approach}, year={2025}, url={https://lenguyen.vercel.app/note/rmu-improv}}References

- The WMDP Benchmark: Measuring and Reducing Malicious Use with Unlearning, Li, Nathaniel and Pan, Alexander and Gopal, Anjali and Yue, Summer and Berrios, Daniel and Gatti, Alice and Li, Justin D. and Dombrowski, Ann-Kathrin and Goel, Shashwat and Mukobi, Gabriel and Helm-Burger, Nathan and Lababidi, Rassin and Justen, Lennart and Liu, Andrew Bo and Chen, Michael and Barrass, Isabelle and Zhang, Oliver and Zhu, Xiaoyuan and Tamirisa, Rishub and Bharathi, Bhrugu and Herbert-Voss, Ariel and Breuer, Cort B and Zou, Andy and Mazeika, Mantas and Wang, Zifan and Oswal, Palash and Lin, Weiran and Hunt, Adam Alfred and Tienken-Harder, Justin and Shih, Kevin Y. and Talley, Kemper and Guan, John and Steneker, Ian and Campbell, David and Jokubaitis, Brad and Basart, Steven and Fitz, Stephen and Kumaraguru, Ponnurangam and Karmakar, Kallol Krishna and Tupakula, Uday and Varadharajan, Vijay and Shoshitaishvili, Yan and Ba, Jimmy and Esvelt, Kevin M. and Wang, Alexandr and Hendrycks, Dan Proceedings of the 41st International Conference on Machine Learning,PMLR, 2024https://proceedings.mlr.press/v235/li24bc.html

- An Adversarial Perspective on Machine Unlearning for AI Safety, Jakub \Lucki and Boyi Wei and Yangsibo Huang and Peter Henderson and Florian Tram\`er and Javier RandoTransactions on Machine Learning Research, 2025https://openreview.net/forum?id=J5IRyTKZ9s

- Unlearning via RMU is mostly shallow, Andy, Arditi Less Wrong,2024https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/6QYpXEscd8GuE7BgW/unlearning-via-rmu-is-mostly-shallow

- On effects of steering latent representation for large language model unlearning, Huu-Tien, Dang and Pham, Tin and Thanh-Tung, Hoang and Inoue, Naoya Proceedings of the Thirty-Ninth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Thirty-Seventh Conference on Innovative Applications of Artificial Intelligence and Fifteenth Symposium on Educational Advances in Artificial Intelligence,AAAI Press, 2025https://doi.org/10.1609/aaai.v39i22.34544

- Improving LLM Unlearning Robustness via Random Perturbations, Dang Huu-Tien and Hoang Thanh-Tung and Anh Bui and Le-Minh Nguyen and Naoya Inoue2025https://arxiv.org/abs/2501.19202

- Latent Adversarial Training Improves Robustness to Persistent Harmful Behaviors in LLMs, Abhay Sheshadri and Aidan Ewart and Phillip Guo and Aengus Lynch and Cindy Wu and Vivek Hebbar and Henry Sleight and Asa Cooper Stickland and Ethan Perez and Dylan Hadfield-Menell and Stephen Casper2025https://arxiv.org/abs/2407.15549

- A Closer Look at Machine Unlearning for Large Language Models, Xiaojian Yuan and Tianyu Pang and Chao Du and Kejiang Chen and Weiming Zhang and Min Lin The Thirteenth International Conference on Learning Representations,2025https://openreview.net/forum?id=Q1MHvGmhyT

- Refusal in Language Models Is Mediated by a Single Direction, Andy Arditi and Oscar Balcells Obeso and Aaquib Syed and Daniel Paleka and Nina Rimsky and Wes Gurnee and Neel Nanda The Thirty-eighth Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems,2024https://openreview.net/forum?id=pH3XAQME6c

- Measuring Massive Multitask Language Understanding, Dan Hendrycks and Collin Burns and Steven Basart and Andy Zou and Mantas Mazeika and Dawn Song and Jacob SteinhardtProceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), 2021

- Aligning AI With Shared Human Values, Dan Hendrycks and Collin Burns and Steven Basart and Andrew Critch and Jerry Li and Dawn Song and Jacob SteinhardtProceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), 2021

- Simple probes can catch sleeper agents, Monte MacDiarmid and Timothy Maxwell and Nicholas Schiefer and Jesse Mu and Jared Kaplan and David Duvenaud and Sam Bowman and Alex Tamkin and Ethan Perez and Mrinank Sharma and Carson Denison and Evan Hubinger2024https://www.anthropic.com/news/probes-catch-sleeper-agents

- Stanford Alpaca: An Instruction-following LLaMA model, Rohan Taori and Ishaan Gulrajani and Tianyi Zhang and Yann Dubois and Xuechen Li and Carlos Guestrin and Percy Liang and Tatsunori B. HashimotoGitHub repository, GitHub, 2023

- HarmBench: A Standardized Evaluation Framework for Automated Red Teaming and Robust Refusal, Mantas Mazeika and Long Phan and Xuwang Yin and Andy Zou and Zifan Wang and Norman Mu and Elham Sakhaee and Nathaniel Li and Steven Basart and Bo Li and David Forsyth and Dan Hendrycks2024

- Catastrophic jailbreak of open-source llms via exploiting generation, Huang, Yangsibo and Gupta, Samyak and Xia, Mengzhou and Li, Kai and Chen, DanqiarXiv preprint arXiv:2310.06987, 2023

- Universal and Transferable Adversarial Attacks on Aligned Language Models, Andy Zou and Zifan Wang and J. Zico Kolter and Matt Fredrikson2023

- Detecting Strategic Deception Using Linear Probes, Nicholas Goldowsky-Dill and Bilal Chughtai and Stefan Heimersheim and Marius Hobbhahn2025https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.03407

- Finding Features Causally Upstream of Refusal, Lee, Daniel Less Wrong,https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/Zwg4q8XTaLXRQofEt/finding-features-causally-upstream-of-refusal

Appendix

A. Dataset

-

The WMDP (Weapons of Mass Destruction Proxy) dataset

[] is a multiple-choice benchmark consisting of one question and four answer options, designed to measure hazardous knowledge in large language models LLM across domains such as biology, cybersecurity, and chemistry. The dataset comprises 3,668 expert-developed questions intended as a representative metric for evaluating and mitigating risks of malicious misuse. -

In biology (referred to as WMDP-Bio), the dataset contains 1,273 questions. These include biotechnology-related risks such as historical instances of bioweapons, pathogens with pandemic potential, construction-related issues (e.g., reverse engineering of viruses), and experimental aspects (e.g., assays for viral properties).

-

In cybersecurity (referred to as WMDP-Cyber), the dataset includes 1,987 questions structured around the stages of a cyberattack: reconnaissance, exploitation, attack, and post-exploitation. WMDP-Cyber evaluates a model’s ability to understand concepts and techniques related to vulnerability discovery, exploit development, and the use of popular offensive frameworks such as Metasploit and Cobalt Strike.

-

Model performance will be evaluated in terms of accuracy on WMDP multiple-choice questions (restricted to WMDP-Bio and WMDP-Cyber). A model trained with unlearning should exhibit reduced accuracy on WMDP while maintaining accuracy on unrelated benchmarks (in the cited work, this is the MMLU dataset

[] [] ). We refer to this overall evaluation as the WMDP Benchmark.

B. More on Probe

Below is data statistics for Probe Training:

| Dataset | Total Samples | Label 1 (Junk) | Label 0 (Non-Junk) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1280 | 1016 | 264 | |

| 320 | 258 | 62 | |

| 400 | 324 | 76 |

The dataset is highly imbalanced. This is understandable given that the base model, Gemma-2-2B, is relatively small. For many challenging (harmful or harmless) questions, the model fails to provide an answer, which is then labeled as junk. With a larger model, this imbalance would likely be reduced.

In training procedure, we apply z-score normalization using the mean and standard deviation computed on the training set, and reuse these statistics for normalization on validation and test sets

Once the best probe is selected, it is used to assign a junk score to activations as:

where is any activation vector, and are the weights and bias of the best-performing probe.

C. Isolating the Junk Direction Methodology

C.1 Dataset

Let denote the dataset used for extracting junk directions. This dataset is split into a training set and a validation set . Specifically, is obtained by sampling from the WMDP dataset, which consists of WMDP-Bio and WMDP-Cyber, corresponding to and (but collectively referred to as ).

The sampling process follows these conditions:

- Samples must not overlap with the detector training dataset of linear probe.

- Samples must not contain questions with the word “which”. The reason is that such questions typically require both the question and the answer context. If used in isolation, they degrade model performance and sometimes lead to empty or anomalous outputs.

- The maximum question length is limited to 1024 characters. This restriction arises both from resource constraints and from the observation that including overly long questions does not affect the final results.

After applying these conditions, 300 samples are drawn from each of WMDP-Bio and WMDP-Cyber, for a total of 600 samples. These are then split into and with an 80%/20% ratio.

In addition, we incorporate out-of-distribution (OOD) data, denoted . This dataset combines three harmful-knowledge benchmarks: AdvBench

C.2 Direction Extraction via Difference-in-Means

Our investigation is built on a central hypothesis: the performance degradation observed in an RMU-unlearned model is not solely due to diffuse changes in its weights. Rather, we posit that RMU instills a specific, learned mechanism.

Causal Hypothesis: For a harmful input, the RMU model adds a specific vector, the junk direction , to the residual stream at a specific layer. This intervention is the primary cause of the model’s junk, low-quality output and the corresponding drop in accuracy on harmful benchmarks.

To extract junk directions, we employ the same method as in

We use the Difference-in-Means

This process is performed for each layer and for the final five token positions of the input prompts, yielding a set of candidate directions.

Warning

The last five tokens (from to ) are selected for the following reasons:

- In the original study by Arditi

[] , eight final tokens were chosen and averaged. This choice was essentially arbitrary. - In the study on refusal directions

[] , the models examined were instruction-tuned and employed structured prompts (e.g.,user:<instruction>model:). Consequently, they selected tokens after the instruction (post-instruction), such asmodel:. However, the models in this thesis are base models without instruction fine-tuning, so such prompt structures cannot be used. - This thesis hypothesizes that information is aggregated in the final tokens. Selecting only the very last token would be overly restrictive. Therefore, the final five tokens are used instead.

C.3 Causal Validation and Selection

From the set of candidate directions, we must identify the one that is most causally responsible for the junk behavior. We use a series of causal interventions, evaluated on a validation set , using the junk score from the linear probe (Appendix B) as our metric.

- Ablation Intervention (Bypass): To test if removing a direction restores coherent behavior in the RMU model, we compute its

bypassscore. We intervene on the RMU model by projecting out the component of its activations that lies along the candidate direction . The optimal direction should maximally reduce the junk score.

- Addition Intervention (Steer): To test if adding a direction induces junk behavior in the base model, we compute its

steerscore. We intervene by adding the direction to the base model’s activations. A potent junk direction should significantly increase the junk score.

- KL Divergence Sanity Check: A true junk direction should be specific to the RMU mechanism and not disrupt the base model’s general knowledge. We verify this by ablating the direction from the base model and measuring the KL divergence between the original and perturbed output distributions. A low KL divergence indicates the direction is inert in the base model, confirming its specificity.

The best junk direction is selected as the candidate that minimizes the bypass score, maximizes the steer score, and maintains a low KL divergence.

D. Relative Gradient Methodology

Let the best junk direction be denoted by , where is the layer and is the token position at which this junk direction is selected. Define:

as the dot product between the residual stream vector of the model , namely at layer and token (the same position where the junk direction is extracted), with the best junk direction for input . Then, the junk gradient is defined as:

i.e., the derivative of the earlier residual streams () with respect to , at token position and input . Here, we choose and (which is the layer and token position of best junk direction).

Intuition

Intuitively, the junk gradient indicates which directions are most responsible for producing the junk direction, and thus which features contribute to its formation. Following

Let denote a dataset sampled from the remaining examples (disjoint from and ). For each of WMDP-Bio and WMDP-Cyber, we define and , respectively.

The aggregated junk gradients at layer are computed as:

In this work, is chosen empirically. This layer is neither too early (close to the embedding layer) nor too late (close to the output), making it a reasonable midpoint for analysis.

Finally, the cosine similarity is computed between these junk gradients and each residual stream vector of the decoder weight matrix from the SAE (Sparse Autoencoder) at layer .